On Wednesday, November 12, 2025, Muni ran its final service using Breda light rail vehicles. The car operated on the J line and was filled with transit enthusiasts for the historic moment.

The Breda LRVs were the second generation of vehicles used on the Muni Metro system. Introduced in the mid-1990s, they served San Francisco for three decades. One of the Breda LRVs will be donated to the Western Railway Museum for preservation. From that point on, all Muni Metro lines will be operated with Siemens LRVs, introduced in the mid-2010s and still being delivered.

Muni Metro is a product of the Great Society vision for rapid transit in San Francisco, partially funded through the voter-approved BART bond. The system featured new light rail vehicles intended to be the national standard, built by Boeing-Vertol, a defense industry manufacturer, as the U.S. transitioned from war to peace. However, the system faced many problems. Rapidly rising construction costs forced a scaling back of the subway, including not building proper turnback tracks in Downtown San Francisco. The vehicles also proved to be unreliable. Additionally, because the vehicles were also built for Boston’s MBTA Green Line along with Muni, many design compromises were made that reduced utility for Muni.

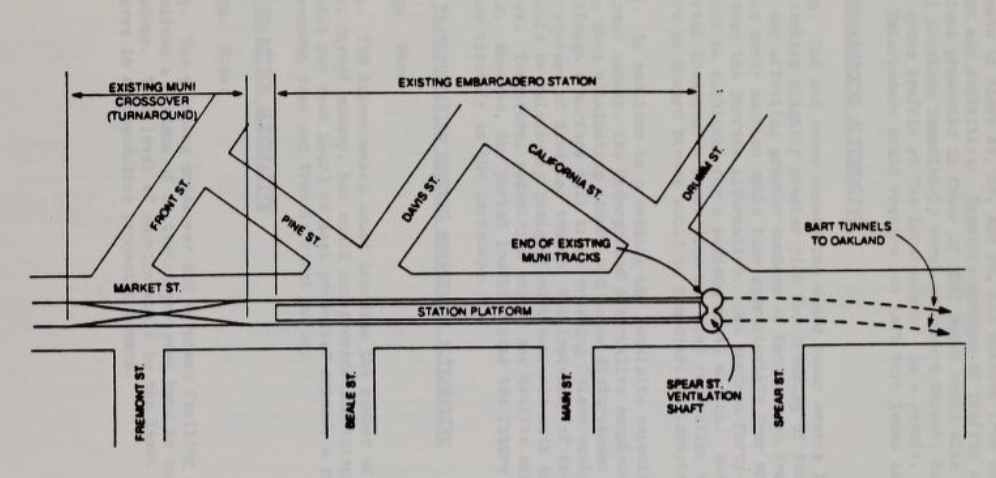

The original Market Street subway for Muni had a stub terminal at Embarcadero Station and a scissors crossover approaching the station. To compensate for the lack of a proper turnback and maintain throughput, cars from different lines were supposed to couple together when entering the subway at West Portal and Duboce Portal, continuing to Downtown as longer 3 and 4 car trains. However, due to surface traffic, the coupling operation proved to be complicated, and frequency was reduced.

Because of the shared design with Boston, the Boeing-made LRVs had only a single door at each end of the vehicle on the right side, which was tapered. This meant that when these vehicles were in the subway, where platforms are level with the vehicle, only the two center doors would open. The vehicles also lacked air conditioning. There were sliding glass windows at the top, and when opened, the cars became noisy inside the subway.

In many ways, Muni Metro struggled to live up to its original vision during its first chapter. In the 1990s, several programs aimed to expand the system and address ongoing issues. These included extending the subway beyond Embarcadero with proper turnback tracks, extending the line beyond the turnback south along the Embarcadero to connect with Caltrain (where the San Francisco Giants eventually built a new ballpark), implementing a new train control system, and introducing new light rail vehicles designed specifically for San Francisco. Breda, an Italian rail car manufacturer, was the sole bidder and was chosen to build the cars in 1991. Prototypes arrived in San Francisco for testing in 1995.

When Breda was introduced, each car cost $2 million, making them the most expensive at the time. The cars were wider and heavier, equipped with more doors and moving steps at each one for level boarding at subway stations. The Breda cars featured a new silver and red livery, while the Boeing LRVs and buses carried the red, orange, and white “Landor” livery. Revenue service began on the J Church line in late 1996.

Despite these improvements, the new fleet faced issues. Residents along the tracks complained about noise and vibrations, prompting the transit agency to fast track a series of track replacement projects to address the concerns.

When the extension from Embarcadero to Caltrain opened in January 1998, Breda cars operated exclusively with the new signaling system, running as a shuttle between Embarcadero and Caltrain with the E designation. The rest of the system continued as before, with all trains terminating at Embarcadero and changing tracks at the scissors crossover. Through service was on hold until the Communications-Based Train Control (CBTC) system was implemented in the subway west of Embarcadero Station later that year. The new CBTC was intended to increase the number of trains in the subway, eliminate the need for train coupling at portals, and improve safety by automating subway operations, similar to rapid transit systems like BART.

On the third weekend of August 1998, a new chapter began for Muni Metro. A new service plan extended the N Judah to Caltrain, with only Breda cars and proof of payment policy, and had other lines using the newly built turnback tracks east of Embarcadero Station. Trains would now operate in automatic mode through the subway.

However, the rollout did not go smoothly. During the first week, some cars struggled to connect with automatic train control at the portals, causing delays. These delays cascaded throughout the system, with some trains stuck in tunnels between stations. Frustrated passengers pulled emergency exit levers to leave stuck trains, causing further delays that were hard to recover from. The severe disruptions led to calls for then–San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown to fire Muni’s General Manager Emilio Cruz, who lacked transit management experience. Some city supervisors were trapped on stalled trains and demanded answers from Muni management.

In a perfect world, these four projects would proceed in coordination, as they had some interdependencies. However, in reality, various elements faced delays at different stages, which impacted other related projects. Delays in Breda car deliveries led Muni to install CBTC signal equipment on most Boeing cars, but not all. The Breda cars equipped with CBTC had an additional mode installed, allowing them to operate under the old fixed block signals as the Boeing cars traditionally did. The turnback facility was built only to work with the new signal system, so once the system change was implemented, Muni couldn’t simply return to the old mode of operation while still using the newly built turnback tracks. Muni contractors had to fix system bugs during the first few weeks until reliability and throughput improved later in September.

With the new signal system, Muni no longer operated three- and four-car trains in the subway, and train coupling no longer took place at West Portal and Duboce Portal. The Breda cars were limited to two-car consists for revenue operations. The Breda cars gradually replaced the Boeings, and all Boeing cars were removed from revenue service in 2001. The silver and red livery of the Breda cars was adopted by Muni for use on buses in the early 2000s.

The Bredas served for the next two decades as Muni expanded the system southward from Caltrain through Bayview along Third Street in 2007, complete with a new railcar maintenance facility. The T Line transformed Mission Bay from a site of deteriorating warehouses into a thriving, transit-oriented community. During the San Francisco Giants’ championship dynasty in the early 2010s, Bredas took riders to World Series games and championship parades. For several years, Breda cars connected riders to buses that took them to Candlestick Park, where the 49ers last played before moving to Santa Clara. The Bredas also took Warriors fans to Chase Center, located along the T Line, beginning in 2019 and to the first Warriors championship parade in San Francisco in 2022.

Despite only marginal reliability improvements over the Boeings, the cars were refurbished in the 2010s to ensure they reached their full service life, as the agency planned to replace the Bredas in the following decade. In 2013, Breda was disqualified from submitting bids for the new vehicles. A year later, Muni chose Siemens, a Germany-based railcar manufacturer with repeat customers in the United States, to build the third generation of vehicles. Meanwhile, some cars had seats removed (double seats per row were converted to single seats) to increase standing capacity.

The introduction of Siemens vehicles in 2017 marked the beginning of the third chapter. The new vehicles offered better technology and reliability, with an interior layout that maximized capacity, despite concerns over seat height and all aisle facing seats with the initial batch. Muni was constructing the Central Subway from Caltrain at 4th & King to Chinatown, and the new vehicles would support the new line and eventually replace the Bredas. When the Central Subway opened in late 2022, only Siemens cars were normally scheduled to operate on the T Line, though on rare occasions Breda cars were dispatched to operate on the T Line in the Central Subway. Since Chinatown Station had been part of Muni’s expansion plans for a long time, the older Bredas with roll signs included Chinatown as a destination.

Throughout Muni’s history with light rail vehicles, there are strong parallels to the evolution of automobiles. The first generation with Boeing resembled American-made cars from the 1970s and early 1980s, often called the Malaise era. Both resulted from public policies and similarly underperformed.

In many ways, the development of Boeing LRVs for Muni Metro and the onset of the Malaise era of automobiles are interrelated. Since World War II, American society, from the federal government down, prioritized freeway construction. American automobile manufacturers pushed for larger cars with more horsepower, while transit was underfunded and rail lines were demolished. The end of the Vietnam War, the start of the environmental movement, and the energy crisis prompted rapid changes in public policy in the 1970s. Part of this shift involved investing in public transit, making it an attractive alternative to cars. Emission and fuel economy requirements led to the Malaise era, when, due to technological constraints, American carmakers generally chose to reduce car size and sacrifice performance. American transit and automobile manufacturing couldn’t compete with foreign makers that continued to receive investment in transit and had long produced smaller cars with better fuel economy.

The second generation with Breda mirrored Italian automobiles, known for their stylish design, but not reliability. The current generation with Siemens is comparable to German cars, emphasizing engineering and durability.

It seems that this time Muni got the light rail vehicles the agency truly wanted, and Breda is becoming part of history, honored for serving passengers from the 1990s dot-com boom, the San Francisco Giants’ World Series dynasty, and through the COVID pandemic.